In Japan, Pondering Over the Traditional Concept of Honoring the Departed

In sultry August nights, Tokyo unfolds its sprawling cityscape, and I find myself strolling through Tama-Reien, the city's vast municipal cemetery. Gravestones and funeral shops populate the path leading to the entrance, giving way to an orderly array of graves that, ironically, harbor a touch of disorder.

Personal plots, meticulously maintained, form a backdrop to those that are neglected—waist-high weeds, crackling headstones, and a mournful silence that disturbs the tranquility. These "abandoned graves" or akihaka have been forsaken by families who have perished or moved on, leaving these resting places untended.

Deeper within the cemetery lies another category of forgotten souls: the "disconnected dead" or muenbo. They are the lonely, kinless individuals who pass away unclaimed, their remains buried in a collective plot by the city authorities. The dense air hangs heavy with a somber atmosphere, strikingly devoid of the usual tender touch of flowers or incense.

My Anthropologist friend Yoshiko Kuga shed some light on the mounting concern that haunts many Japanese—fearing the fate of joining the disconnected dead. Kodokushi, or lonely death, has become a growing concern, with its roots deeply intertwined with changing social dynamics in Japan.

For decades, I've devoted myself to studying social hierarchies, gender, and capitalism in urban Japan. Yoshiko and I crossed paths during an earlier fieldwork, forming a bond that led me to embark on a new research journey into the evolving mortuary practices in modern Japan. The specter of hungry ghosts roaming the land, bereft of a final resting place, is a potent symbol of the impending crisis.

Historically, the majority of Japanese could expect their remains to find their way to an ancestral plot, attached to a Buddhist temple, where the spirits would be cared for by their kin for at least 33 years. However, shifting demographics and socioeconomic factors have shaken the foundations of this tradition.

Post-World War II Japan saw a massive urban migration from the countryside and changes to patrilineal kinship laws, resulting in an unstable family-based mortuary system. The trends have accelerated in recent years due to myriad factors such as smaller households, extensive urbanization, a decrease in marriages and cohabitation, weakening ties to Buddhist institutions, and economic struggles since the 1990s.

In a world where relying on one's family to care for them at death is no longer a realistic option for many Japanese, the undesirable fate of the disconnected dead lurks on the horizon. Reports of abandoned graves, especially in rural areas, abound—accounting for as much as 40% of the structures in some cemeteries. Lonely death, or kodokushi, is set to become a grave concern in a country where one-third of the population now lives alone and the national population continues to dwindle with each passing year.

Yoshiko and I visited her family's grave in a public cemetery later that summer. Caring for the dead entails frequent visits to the grave on anniversaries and holidays where acts such as washing the gravestone, lighting incense, and offering prayers and fresh flowers are customary. Yet, even those with family graves like Yoshiko are not immune to the risk of their plots becoming overgrown and "messy" once the family line dies out or moves away.

Facing the prospect of being reinterred in a collective plot for the disconnected dead, Yoshiko is considering transferring the contents of her ancestral grave to an urban, indoor facility called a columbarium. These facilities cater to those unable or unwilling to manage family graves, ensuring that they find solace in a place where they can be surrounded by their family's memories.

This shift towards the commodification of death has given rise to a plethora of creative innovations—such as robot priests, automated columbarium, and green burials—all of which provide alternatives to the family-based mortuary system. The swing towards the family-less dead has opened new avenues in Japan, where choices ranging from rocket send-offs to green burials can now be arranged, albeit for a fee.

Navigating the complexities associated with 21st-century Japan's family-less dead is a dizzying journey, riddled with ambiguities and tensions. In my recent book, Being Dead Otherwise, I delve into this rapidly evolving deathscape, incorporating snapshots from fieldwork that offer insights into the changing practices surrounding care for the dead.

Editors' note: This essay is an adaptation from the author's book, Being Dead Otherwise.

GLIMPSES OF THE DEATHSCAPE

All photos in the series are courtesy of Anne Allison

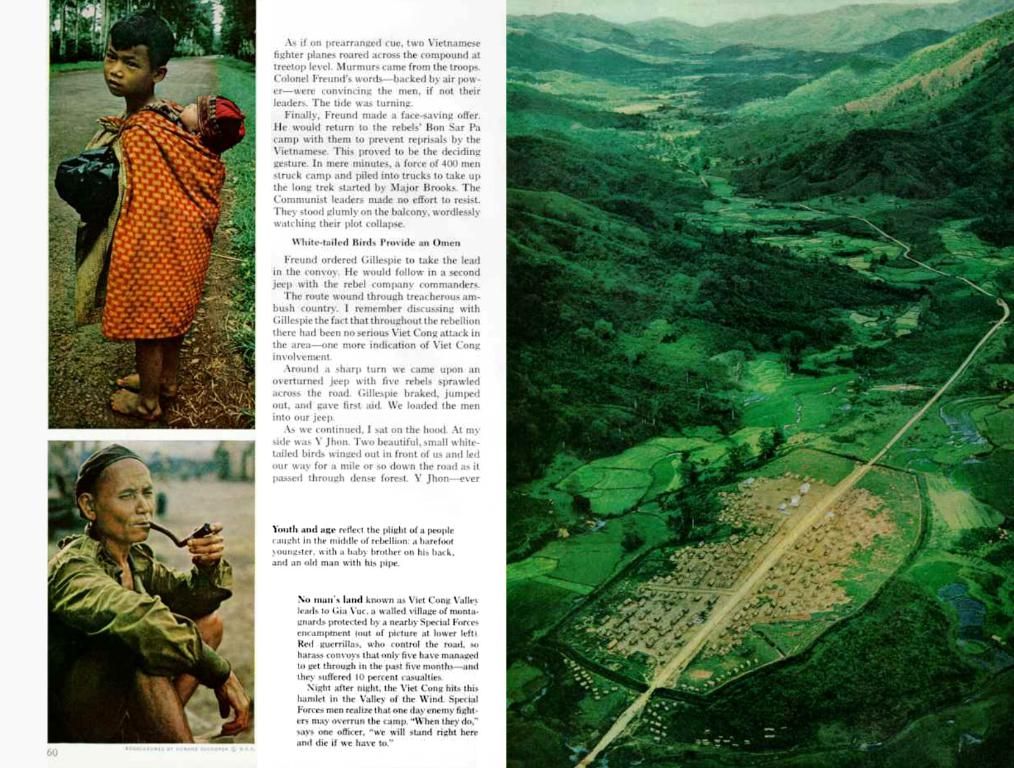

Caring for the Grave: In traditional Japanese mortuary systems, family members pay annual fees to maintain the gravesite and perform various rituals such as lighting incense, offering prayers, and placing fresh flowers. Each family has a designated plot, which is passed down through generations.

A Nighttime Wake: The wake is held the evening before the funeral and is attended by friends and family members. During this solemn event, relatives give gifts known as bereavement money, symbolizing both condolences and a financial burden shared among the mourners.

At the Crematorium: By law, all corpses must be cremated unless the deceased specifically opposes it for religious reasons. Consequently, crematoriums are busier than ever due to the rapidly aging population. With a wait time of up to two weeks, some families opt for temporary storage units, colloquially known as corpse hotels.

Observing Obon: Obon is a Japanese Buddhist festival to honor deceased ancestors. Lasting for three days, it is characterized by music, feasting, and dancing, with families cleaning and offering food to the ancestors’ graves.

Muenbo (Grave for the Unconnected): Abandoned, unclaimed graves are referred to as “empty graves" or akihaka. Cemeteries in Japan have rules in place to reclaim these neglected plots after a specified period. Many now post notices warning visitors of this possibility.

A Collective Grave-by Choice: Some Buddhist temples now offer burial to anyone, relaxing the traditional requirement of being a parishioner or having a kin/successor to be buried there. These temples provide care for the deceased, ensuring they do not become disconnected souls in the future.

Cherry Blossom Burial: As more Buddhist temples struggle financially, they have begun to offer their services, cemeteries, and columbaria to non-parishioners. This poster advertises a one-time fee and eternal memorial service under cherry blossoms, appealing to those seeking alternatives to the traditional family-based mortuary system.

Morticians in Training: The ENDEX JAPAN convention brings together businesses from around the world, showcasing the latest trends in the mortuary industry. Attendees can join workshops, learn about innovative products, and hone their skills in various aspects of mortuary care.

Cleaning after Death: Japan's burgeoning death market includes companies that specialize in cleaning residences of the deceased. Companies like Keepers, pictured here on a job, have seen an increase in demand due to the rise in kodokushi.

Miniature Scenes of Lonely Dead: Driven by her experiences following her father's lonely death, Miyu Kojima started crafting miniature dioramas of the death scenes she was commissioned to clean. These detailed and moving model scenes offer a poignant glimpse into the emotional impact of loneliness and isolation in death.

The ongoing evolution of mortuary practices in modern Japan has led to an increased focus on health-and-wellness and mental-health aspects, as evolving demographics and socioeconomic factors challenge traditional family-based arrangements. For example, Yoshiko Kuga, the anthropologist friend mentioned earlier, is considering transferring her family's grave to an urban, indoor columbarium, where she can be surrounded by her family's memories and maintain a connection even after her lineage ends. Furthermore, the rise of kodokushi, or lonely death, and the increasing number of disconnected dead in collective plots, has sparked growing concern among Japanese citizens about the health and well-being of the deceased and their families.